Linear Regression

One common problem in Statistics is to learn a functional relationship between independent variables and dependent variable. For example, we may want to know how the price of houses varies with the area of the land, the total size of the house and various other criteria. In this particular case, the price of the houses is the dependent variable, also often referred to as the response variable while the area of the land and total size of the house are the independent variables, also known as the attribute variables.

We will first begin with linear modelling, that is, given a set of attributes, we want infer a linear relationship between the attributes and the response. The function which we want to fit is typically governed by a set of parameters, say $\theta_{i}$. However, before indulging into this topic, it is worth discussing linear and non-linear models.

The equation \begin{align} y=\theta_{0} + \theta_{1}x + \theta_{2}x^2 \end{align} is a linear model model because it is linear in the parameters $\theta_{i}$. In contrast, the model \begin{align} y=\textrm{sin}\left(\omega x + \phi\right) \end{align} is a non-linear model since it includes parameters $\left(\omega,\,\phi\right)$ which are non-linear.

Maximum Likelihood Method

Suppose, we now want to fit a polynomial $f\left(x\right)$ of order $M$ to some observed data $\left(x_{i},\,y_{i}\right)$ where $i=0,\,1,\,2,\ldots N-1$. We further assume that they are corrupted with Gaussian noise, $\sigma_{i}$. Then, each observed datum can be described by a Gaussian: \begin{align} \mathcal{P}\left(y_{i}\left|\boldsymbol{\theta}\right.\right)=\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma_{i}^{2}}}\,\textrm{exp}\left[-\dfrac{1}{2}\left(\dfrac{y_{i}-f\left(x_{i}\left|\boldsymbol{\theta}\right.\right)}{\sigma_{i}}\right)^{2}\right] \end{align} where $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ is the set of parameters $\left(\theta_{0},\,\theta_{1},\ldots \theta_{M}\right)$. For simplicity, we will explain this method by using a linear fit to the data, that is, $f\left(x\left|\theta_{0},\,\theta_{1}\right.\right)=\theta_{0}+\theta_{1}x$. Assuming that the data point is independent from each other, the likelihood is simply a product of the individual probability distribution of the above.

We will define the vector $\mathbf{b}$ as: $$ \mathbf{b=\left(\begin{array}{c} \frac{y_{0}}{\sigma_{0}}\\ \\ \vdots\\ \\ \frac{y_{N-1}}{\sigma_{N-1}} \end{array}\right)} $$ and the design matrix, $\mathbf{D}$ as: $$ \mathbf{D}=\left(\begin{array}{cc} \frac{1}{\sigma_{0}} & \frac{x_{0}}{\sigma_{0}}\\ \\ \\ \\ \frac{1}{\sigma_{N-1}} & \frac{x_{N-1}}{\sigma_{N-1}} \end{array}\right) $$

Therefore, the likelihood (ignoring the pre-factor) can be written as: \begin{align} \mathcal{P}\left(\mathbf{y}\left|\boldsymbol{\theta}\right.\right)\propto\textrm{exp}\left[-\dfrac{1}{2}\left(\mathbf{b-\mathbf{D}\boldsymbol{\theta}}\right)^{\textrm{T}}\left(\mathbf{b-\mathbf{D}\boldsymbol{\theta}}\right)\right] \label{eq:likelihood} \end{align} Our aim is to maximise the likelihood. Therefore, the derivative of the likelihood with respect to the parameters should be equal to zero. However, maximising the likelihood is equivalent to maximising the log-likelihood since the latter is a monotonic transformation applied to the likelihood. Some useful tricks when differentiating with respect to a vector are given below.

$$ \dfrac{\partial\mathbf{A}\mathbf{x}}{\partial\mathbf{x}}=\mathbf{A} $$ $$ \dfrac{\partial\mathbf{x}^{\textrm{T}}\mathbf{A}}{\partial\mathbf{x}}=\mathbf{A}^{\textrm{T}} $$ If $\mathbf{A}$ is a symmetric matrix, $$ \dfrac{\partial\mathbf{x}^{\textrm{T}}\mathbf{A}\mathbf{x}}{\partial\mathbf{x}}=2\mathbf{x}^{\textrm{T}}\mathbf{A} $$ For further details, see Wikipedia or the Matrix Cookbook.

Using Equation \eqref{eq:likelihood} and the above useful identities,

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{\theta}_{\textrm{MLE}}=\left(\mathbf{D}^{\textrm{T}}\mathbf{D}\right)^{-1}\mathbf{D}^{\textrm{T}}\mathbf{b} \end{align}

The matrix $\mathbf{C}=\left(\mathbf{D}^{\textrm{T}}\mathbf{D}\right)^{-1}$ is called the covariance matrix and gives the standard uncertainties associated with the parameters determined. In particular, the diagonal elements of this matrix give the variances of the parameters while the off-diagonal elements give the covariances between the parameters $\theta_{j}$ and $\theta_{k}$. Hence, the errors on the parameters are equal to the square root of the diagonal elements of the covariance matrix $\mathbf{C}$.

Example - A Physics Problem

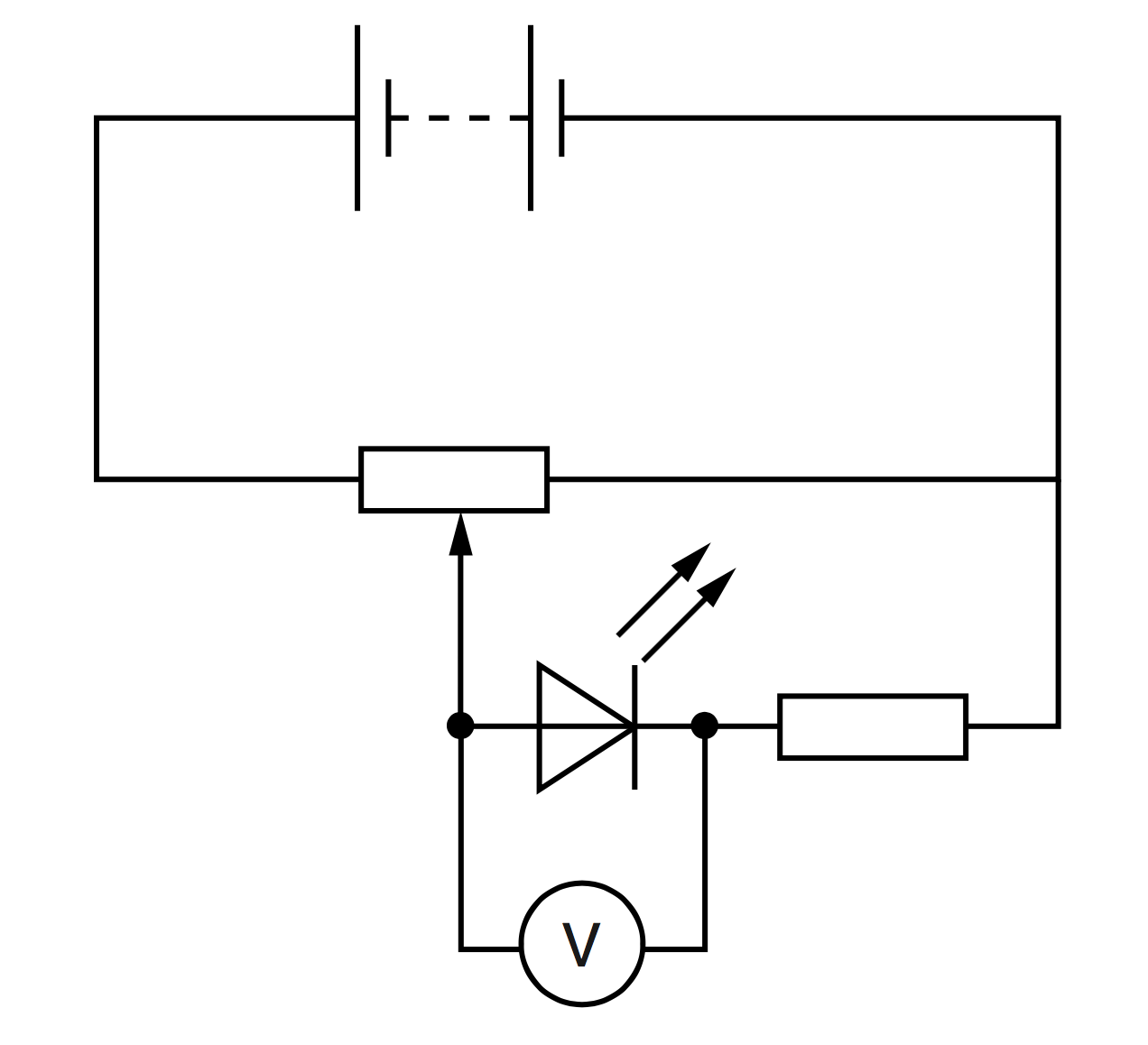

We will use the above explanation to answer a Physics problem (Physics 9702 November 2016 Paper 52). A student is investigating the characteristics of different light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Each LED needs a minimum potential difference across it to emit light. The circuit is set up as shown on the left.

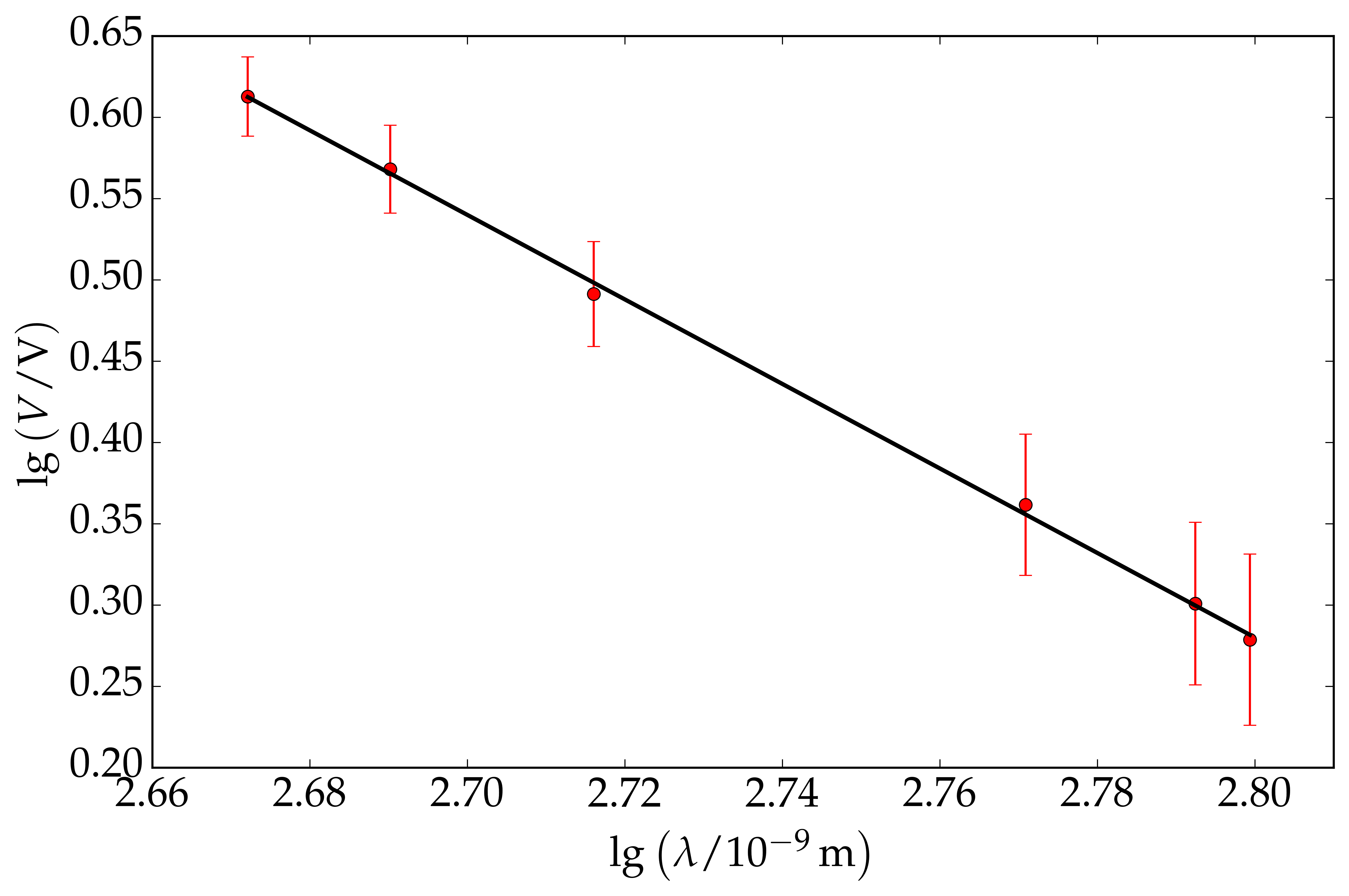

The potentiometer is adjusted until the LED just emits light. The potential difference $V$ across the LED is measured. The experiment is repeated for LEDs that emit light of different wavelength $\lambda$. It is suggested that $V$ and $\lambda$ are related by the equation \begin{align} V=p\lambda^{q} \end{align} where $p$ and $q$ are constants. Therefore, if we are to plot a graph of $\textrm{lg }V$ on the $y$-axis against $\textrm{lg }\lambda$ on the $x$-axis, the gradient of the straight line will correspond to $q$ while the $y$-intercept to $\textrm{lg }p$. To be explicit, $$ \textrm{lg }V = q\,\textrm{lg }\lambda + \textrm{lg }p $$

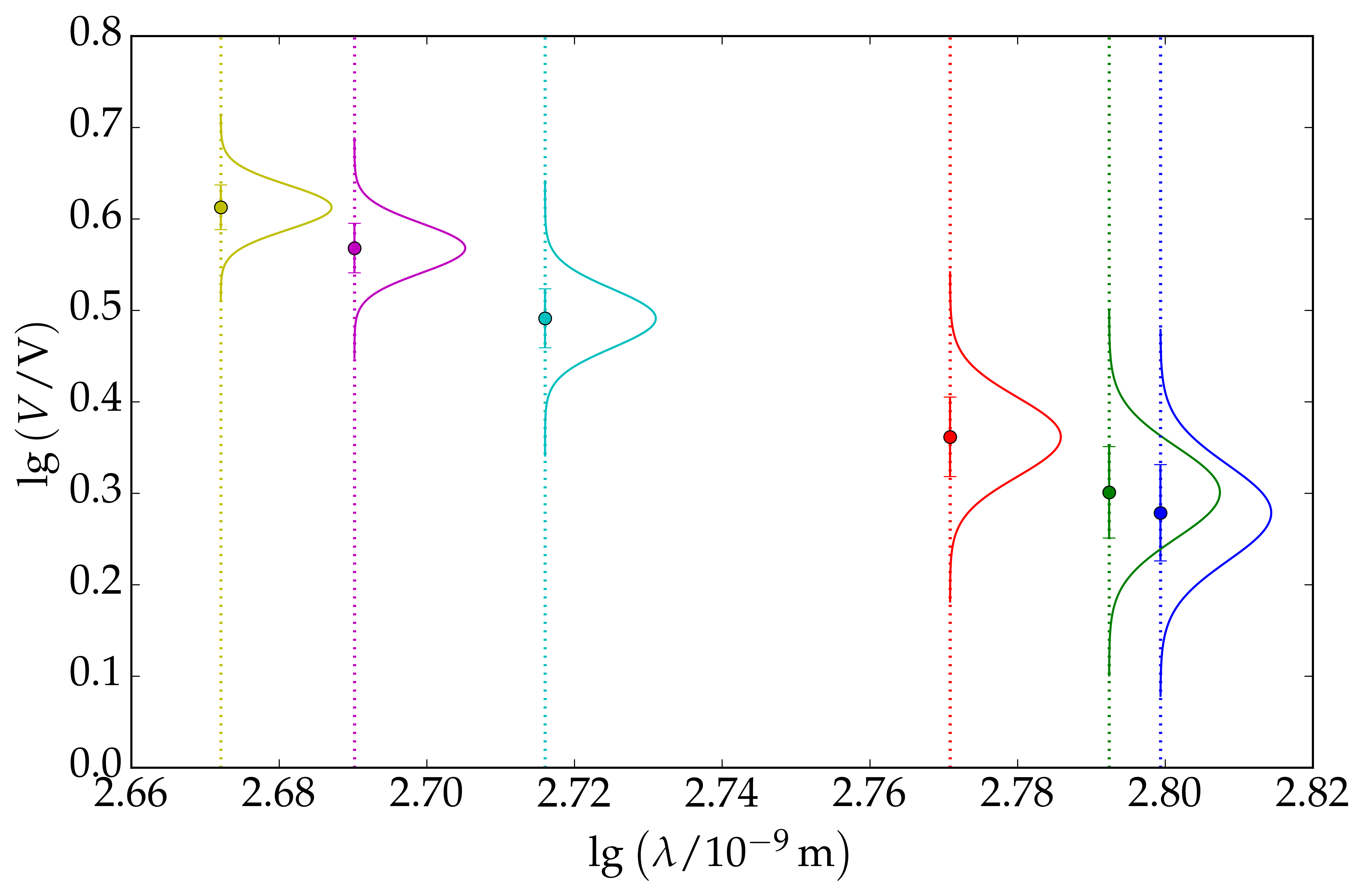

The values of $V$ and $\lambda$ are given in the table below and we also calculate $\textrm{lg }\lambda$ and $\textrm{lg }V$, with its associated error. The error in $\textrm{lg }V$ is: $$ \sigma_{\textrm{lg }V} = \dfrac{\Delta V}{V} $$ See this link for further detail. For this problem, we calculate $\textrm{lg }\lambda$ and $\textrm{lg }V$ to two decimal places. We assume that each data point is Gaussian distributed with mean, $\mu=\textrm{lg }V$ and standard deviation, $\sigma = \sigma_{\textrm{lg }V}$. An illustration of this assumption is shown on the right. We are now ready to plot the graph of $\textrm{lg }V$ versus $\textrm{lg }\lambda$. We find that the gradient is equal to $2.60$ while the $y$-intercept is equal to $7.56$.

| $\lambda/10^{-9}$ m | $V/\,\textrm{V}$ | $\textrm{lg}\left(\lambda/10^{-9}\,\textrm{m}\right)$ | $\textrm{lg}\left(V/\,\textrm{V}\right)$ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 630 | $1.9\pm0.1$ | 2.80 | $ 0.28\pm0.05$ |

| 620 | $2.0\pm0.1$ | 2.79 | $0.30\pm0.05$ |

| 590 | $2.3\pm0.1$ | 2.77 | $0.36\pm0.04$ |

| 520 | $3.1\pm0.1$ | 2.72 | $0.49\pm0.03$ |

| 490 | $3.7\pm0.1$ | 2.69 | $0.57\pm0.03$ |

| 470 | $4.1\pm0.1$ | 2.67 | $0.61\pm0.02$ |

Moreover, the covariance matrix is: $$ \mathbf{C}=\left(\begin{array}{cc} 0.670 & -0.258\\ -0.258 & 0.095 \end{array}\right) $$ Hence, $$ q=-2.60\pm0.84 $$ $$ \textrm{lg }p = 7.56\pm0.31 $$

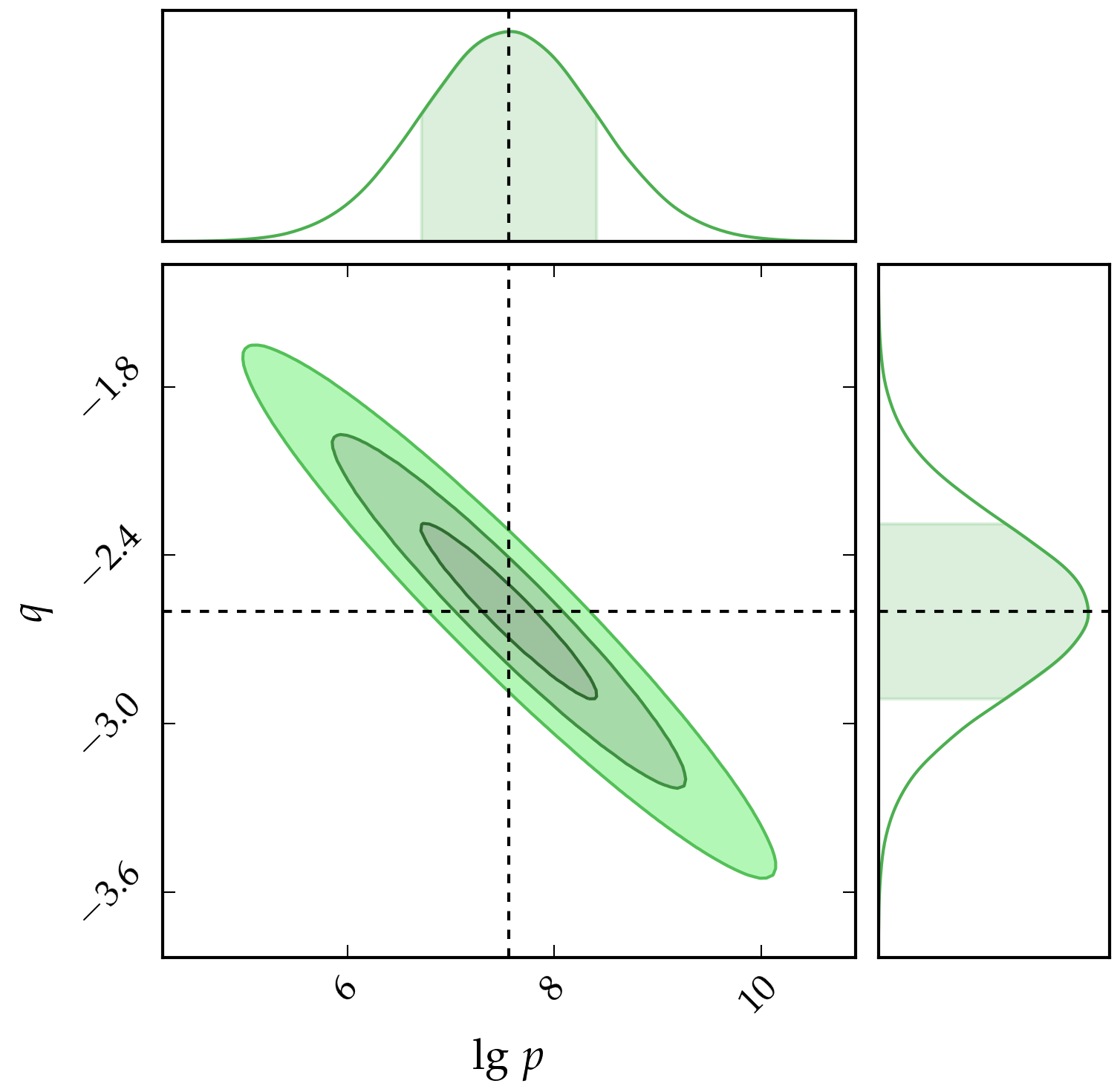

Therefore, in short, the estimates of $p$ and $q$ are $3.61\times10^{7}$ and $-2.60$ respectively. We can also learn about the correlation between the two parameters from the covariance matrix. In particular, since the off-diagonal elements are negative, this implies that the two parameters are negatively correlated, that is, an increase in one parameter results in the decrease of the other. This is illustrated in the figure below, which also shows the credible intervals at $1\sigma$, $2\sigma$ and $3\sigma$. It is also worth mentioning that the distribution of the two parameters $\left(\textrm{lg }p,\,q\right)$ are Gaussian distributed since we are working with a linear model. In addition to this, we can use the values of $p$ and $q$ to estimate the minimum potential difference required if a different diode is used, for example, a diode emitting a wavelength of $950$ nm.

Summary and Conclusion

In this post, we have gone through one method of inferring parameters, namely, the Maximum Likelihood Estimator. We have also provided an example to illustrate this method. It does provide a good estimate of the parameters along with their associated errors. Moreover, we can also learn about the correlation between the parameters using the covariance matrix.

In addition to this, if we had some prior information on the parameters, then the concept of Bayesian Statistics is invoked. The concept is not very different, except that we would have had a prior probability distribution for each parameter. Additionally, instead of finding the MLE, we will end up having the MAP, that is, the Maximum a Posteriori estimates of the parameters. If uniform distributions are assumed, then the MAP coincide with the MLE.